Softening the edges of engineering design

FROM THOROUGH MAGAZINE: The principle of co-creation helps engineers discover solutions that will work at a technical - and human - level.

By Kathy FitzpatrickIt was not Justin Burns’ typical experience working with an engineering design team. This time, he felt like an equal participant.

At the Dakota Dunes Casino south of Saskatoon, four environmental engineering students from the University of Saskatchewan College of Engineering (USask Engineering) and the chief and several councillors from James Smith Cree Nation took part in a feast and discussed potential designs for a new subdivision.

“It was very impressive to see a lot of the designs that came from that meeting,” said Burns, one of the councillors from the First Nation, located 175 kilometres northeast of Saskatoon.

The gathering was one stage in the students’ capstone design project, a graduation requirement that sees them work to solve a client’s real-world engineering problem. The environmental engineering team working with the James Smith community employed an approach called co-creation. The concept has been enthusiastically embraced and promoted at USask Engineering by Dean Suzanne Kresta.

“What I’m looking for is a change in culture,” she explained.

In co-creation, engineers take the time in the first phases of a design project to thoroughly understand the values, wishes and priorities of the community, rather than just consider economic and environmental factors. The initial time spent helps to better define the problem engineers are asked to solve. And feedback as the project continues helps ensure the end result meets the community’s needs.

Too often in the past Burns felt like an outsider when he met with consulting engineers and their professional colleagues. While the professionals were wrapped up in their own ideas, Burns and other community members struggled to put forward theirs. The end result was sometimes much grander and more expensive than what the community was looking for, Burns recounted.

The tendency of engineers to slide into saying things like ‘we have to make the public understand,’ rather than undertake meaningful consultation with the community, is part of what needs to change, Kresta observed.

“We can’t do that. It can leave people with the feeling that they are not respected or heard. The wisdom of Elders and members of the public with lived experience can add to our understanding of what the solution might look like.”

She quickly adds that co-creation is not always easy or comfortable, and can be slow and complex and aggravating, but is the “path to sanity” because it acknowledges the importance to human beings of having autonomy and being heard.

James Smith Chief Wally Burns would most likely agree. “Building a community takes a lot of effort, time and patience,” he said. "We as leadership are working to design a community that our people feel at home in, with their wishes and needs in mind. This includes health, safety and fostering a sense of community, pride in culture, and togetherness.”

Kresta first became aware of the need for co-creation through her daughter’s involvement with the non-governmental organization Engineers Without Borders.

“When you do development work, if you don’t meet people where they are and go through this initial process, you will do the wrong things,” Kresta noted. “And so we have thousands of wells that are dug in Africa without the gaskets to keep the pumps working, because we forgot to see if there were technicians and to identify people who could be responsible for maintaining the pumps.”

Assistant Professor Lori Bradford is building on Kresta’s initiative through her work as Canada Research Chair in Social and Cultural Decision Making in Engineering. She became interested in the subject from her experience working with Indigenous partners through USask’s Safe Water for First Nations Working Group. Bradford discovered how narrow funding formulas and the engineering practices they encourage can lead to choices destined to fail.

She said James Smith Cree Nation is one of several First Nations communities “where culturally inappropriate infrastructure is put in because engineers say it’s the optimal solution, not because it’s the solution the community wants.” Engineers will have to study social and cultural values and include them in their decision-making and design, Bradford said, “or we’re going to commit ongoing colonization. We’re going to put Western solutions on reserves when they’re not invited.”

She noted the shift in mindset is happening faster in civil and environmental engineering than in some other disciplines. That is due to Canada’s Impact Assessment Act, brought into force in 2019, which mandates the inclusion of health, cultural, and social impacts in assessing major projects and projects on federal land or outside of Canada.

It was through the working relationship between Bradford and James Smith councillor Justin Burns that the opportunity for the capstone project came up. Burns was brainstorming about the development of 80 to 125 new lots, and Bradford and colleague Terry Fonstad offered to have some of their students work on it. The students were asked to look at the current state of community design in Indigenous communities, and through real engagement with James Smith Cree Nation over several months, see how those designs could be altered to fit specific needs.

"It's a pleasure collaborating with teams like this who help make our vision a reality," Chief Burns said.

The community is also building a police station and a wellness centre. “Band leadership, along with support from various levels of government, are looking forward to improving housing, infrastructure, and services to meet the needs of our growing population with safety, health and culture at the forefront of all expansions,” he added.

Bradford aims to have students continue to do more such projects, building what’s learned from them into the Engineering curriculum. Sharing successes will also help shift the culture, she added.

Student Akash Mundi has embraced whole-heartedly the opportunity for growth that co-creation presents. He notes even though environmental engineering is already more of a social-sided discipline “still it was a stretch.”

As one of the four capstone project team members, Mundi invested time listening to Indigenous people and reading about Indigenous history and communities, including their art and music.

“We wanted to almost replicate more of an artistic mindset, because that is where the emotional and spiritual impact of things becomes a lot more apparent,” he explained.

The team also drew on social sciences for insight into community interaction. “We engineers do not have a clue about this, you know. I can design a culvert, a landfill, but if somebody thinks a building or a neighbourhood is ugly how am I supposed to fix that? So that was quite the learning curve,” Mundi said.

Team members also talked to urban planning students about such things as ‘what happens if the roads are made narrower or wider?’ and, if those roads are made of different material ‘does it affect anything?’

“We would try to place ourselves within such a community,” Mundi explained.

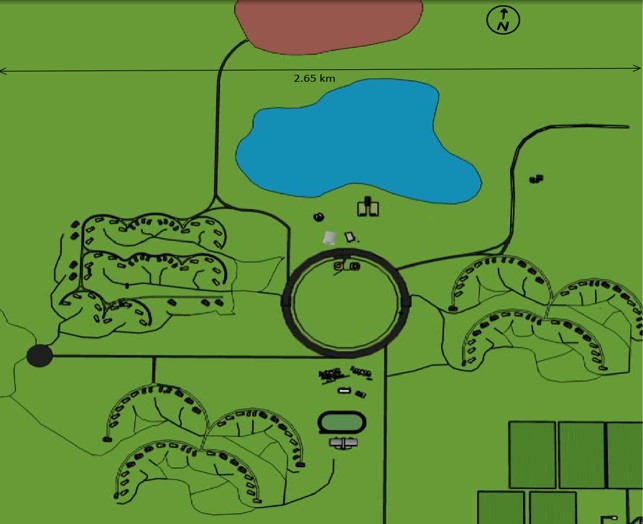

One aspect the students sought to address was the dislike by many community members for the current townsite and their desire not to replicate it. Chief Burns explained the heart of the community is tightly built along one corridor, a layout developed a few decades ago without much consultation with the community.

Engineering consultants are trained in optimization, Bradford noted. The result is often a neighbourhood built in a tight grid pattern to keep the cost of service connections as low as possible. But that urban-like design does not fit with the way the James Smith community lives. Many prefer to live more spread apart in the traditional way, Chief Burns noted.

The capstone team spent the first four months of their project just listening to what the community wanted. Together, they came up with a list of four priorities. In their second semester, the team came back with a variety of designs to present to the community and gather further feedback.

One of the most popular, Mundi recalled, is a semi-circle of houses facing each other, a design that gives each household more space while still inviting community interaction.

Along with learning not to let his biases creep into a design, Mundi said the experience has also taught him to practise “organic social skills” such as picking up on body language and other cues. He learned much from the informal style of James Smith members, who would often joke as they sat at a round table “but they were getting the points across.”

“In a way they use empathy as a communication tool and that is so alien to an engineer,” Mundi continued. “You think ‘Oh I’m solving a problem’ but the core problem is the human happiness that you’re trying to create in the end.”

It’s this shaping of engineering students into “three-dimensional human beings” that Dean Kresta is aiming for. “Starting them from that place of respect and inquiry and understanding actually humanizes their educational experience,” she said.

Meanwhile, she is building greater acceptance for co-creation among those in the profession responsible for regulation and accreditation, through her work in a national project called Futures of Engineering Accreditation.

Within the college itself, she hopes to see this approach extend into the ethics and professionalism course, design courses, and into the Ron and Jane Graham School of Professional Development where they already explore negotiation and conflict resolution.

“There’s a tremendous scope in this college to continue to develop those ideas, and that leaves me hopeful for the future.” Kresta said.

Together we will support and inspire students to succeed. We invite you to join by supporting current and future students' needs at USask.