USask Engineering answers the call

College of Engineering shows it's ready to step up and collaborate - at every level - with an industry partner.

By Donella HoffmanAs the COVID-19 pandemic started overwhelming health-care systems around the world in March 2020, University of Saskatchewan (USask) College of Engineering alum Jim Boire (BE’96) decided that designing and manufacturing an emergency-use ventilator (EUV) was simply the right thing to do.

And that’s what he and his team did. Within nine months, their ventilator was developed and had received COVID-19 Medical Device Authorization from Health Canada.

Along the way, Boire’s company became Saskatchewan’s first licensed medical device manufacturer – an accomplishment he’s now building on.

And the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Engineering (USask Engineering) showed it was ready to step up and collaborate – at every level – with an industry partner.

“What do you need?”

In mid-March 2020, shortly after the World Health Organization declared that COVID-19 was a global pandemic, Boire received a phone call from his daughter, an ICU nurse at Royal University Hospital in Saskatoon.

There may not be enough ventilators, she told him. At that time, North Americans had been hearing about doctors in Italy who were rationing life-saving health-care and equipment, including mechanical ventilators, which take over the work of breathing for a patient and get more oxygen into their lungs. (See graphic.)

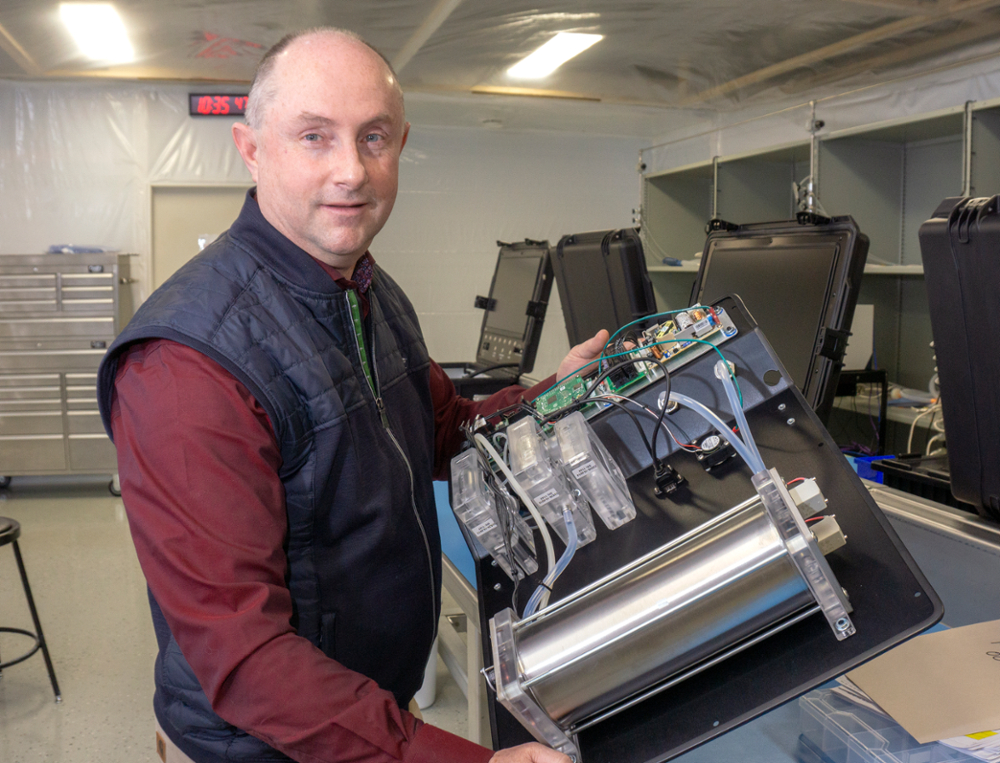

Boire, president of Saskatoon-based RMD Engineering Inc., felt he had to do something. He and his team began developing a ventilator, which ultimately became the EUV-SK1.

It was a decision that not only impacted his company, but his career.

“It was the right thing to do,” he says. “If you know you have a team of people that can pull a rabbit out of a hat, you can’t not act.”

The first prototype was built in less than a week and put RMD on the path to becoming Saskatchewan’s first medical device manufacturer, via its subsidiary, One Health Medical Technologies.

Though Boire knew what his team was capable of, he recognized that it wouldn’t be enough to get his foot in the door with USask and the College of Medicine – home to the end users he needed to consult.

“If you’re going to start knocking on doors, asking people to trust you, you have to have some credibility.”

In late March, he called Suzanne Kresta, Dean of the College of Engineering, and invited her out to see RMD’s ventilator project.

It wasn’t their first meeting. Boire was one of the industry representatives invited to sit in on candidate presentations in 2017 during USask’s search for a new engineering dean. “She was very forward-thinking and very progressive,” he recalls.

In addition to her work as an academic, Kresta is a chemical engineer who is recognized internationally for her expertise in industrial mixing. It was this knowledge of manufacturing processes that Boire wanted to capitalize on; ultimately seeking to have Kresta validate RMD’s capacity to develop a medical device.

“I approached Suzanne, one engineer to another, and asked if she would afford us a visit to talk about what we were doing. And that's the way she is, she just said, ‘OK, you have my attention. What do you need from me?’ ”

On a Sunday night in late March, Kresta spent three hours at RMD, touring the facility and learning about the ventilator from Boire. She was impressed enough to conclude that the project was feasible and saw there was a role for USask expertise. That night, she called Preston Smith, Dean of the College of Medicine, putting in motion a collaboration that would reach into several corners of the university.

“This project has been so aligned with Saskatchewan values,” Kresta says. “There was such a high level of partnership and innovation – because each of the players saw that there was a problem to solve and we believed we had the resources right here to solve it.”

Boire says Kresta’s support provided the credibility needed to open more doors at USask.

“None of this would have happened without her, and I know she says she didn't do anything but she did. It's being that person, in that role, that makes her own decision and trusts you. That was very, very appreciated.”

“We just build things and design things that work.”

Along with the urgency that arose as the COVID-19 pandemic intensified, there was another complication: with Chinese digital component supply chains severely disrupted, Boire and his team found that many of the parts they needed were suddenly unavailable.

In the course of solving this immediate problem, Boire took the initial steps that have ultimately had a huge impact on RMD’s strategic direction.

RMD quickly adapted and simplified the design of the EUV-SK1. Rather than using turbines to control flow, they use proportional solenoids instead. There are only four moving parts in the ventilator.

While the first prototypes used outsourced solenoids, there was no guarantee RMD could secure ongoing supply at a reasonable price.

So, as many generations of Saskatchewan farmers and entrepreneurs have done when confronted with a problem, Boire came up with his own solution: RMD would design and manufacture its own solenoids.

Boire was a journeyman machinist before going back to school to get his engineering degree and knew the equipment he needed to start producing solenoid components. He specifically had in mind a 1970s-era Hardinge-brand lathe, highly sought after because of its precision, accuracy and versatility.

Though Boire had tracked down and purchased his own Hardinge machine for RMD, it wouldn’t be delivered until May. He also knew that the Engineering Shops at the College of Engineering had two of the lathes in question, purchased new back in the 70s for about $60,000 apiece.

“No one makes a lathe that’s comparable,” says Blair Cole, Engineering Shops manager, of the prized equipment.

With his machining background, Boire understood their capabilities as well. “Those lathes are an icon in the industry. You can do things on them that you can’t do with modern lathes,” he says, referring to their ability to produce very small items to very precise specifications.

With the lathes sitting idle after the college had ceased in-person operations in March, Boire struck a deal to borrow them until his own arrived.

In lieu of paying a rental fee for the seven weeks it used the lathes, RMD donated equipment back to the Engineering Shops: lathe tools and accessories that staff had had on their wish lists for years.

While lending out the college’s equipment is not an everyday practice, Kresta says the timing made sense and considers it an important part of the college’s collaboration with RMD.

“Timelines are important in business and we understood this was critical to keep the project moving,” she says.

The solenoids are just one example of RMD’s resourceful approach to sourcing components for the initial EUV-SK1: everything from flow metre valves to the electrical circuit boards were made in Saskatchewan.

“It’s important to have this capacity here. This is where you've got all the ingenuity of every farmer in every corner of this province, so there's things that we can do here because for some reason we don't believe in those boundaries and we just build things and design things that work.”

“This experience has made us better at what we do.”

The halls of the College of Engineering are usually buzzing during March as students push to finish quizzes, assignments and labs before finals hit.

But in March 2020, in-person activity screeched to a halt when USask closed its campus.

Employees like Chandler Janzen, a support engineer in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE), suddenly found themselves at home.

He is one of five professional engineers who works in the electrical and computer engineering labs. Each runs the undergraduate lab class in their area of specialization and supports students when needed, in addition to providing technical advice for grad students and researchers.

After helping students complete their final lab remotely, Janzen and his colleagues planned to spend the coming months converting in-person labs for online delivery.

Then a former student, now working at RMD, reached out for help with the electrical circuit boards they were designing for the new project the company was working on – a made-in-Saskatchewan ventilator.

“Working on a ground-up design is a very different process and they were feeling like they had hit the wall,” says Janzen. “So, they were looking for some mentorship and technical advice, and some manpower to help them get through what they were stuck on.”

With the college labs at a standstill, three ECE support engineers were seconded to RMD: Janzen, who specializes in computer engineering; Rory Gowen, whose speciality is digital signal processing, and Peyman Pourhaj, who specializes in analog and digital microwave sensors.

Given the tight timelines that RMD had given itself, work on the project was intense, but enjoyable, Janzen says.

“It was a good experience. I was always thinking about it, even when I got home. It was like, ‘OK, what’s the next step.’

“And it was really nice, because of the pace of the project, we got to see the design get all the way through to completion. It was neat seeing it happen in such a short amount of time.”

The ECE engineers, along with RMD’s team, developed the circuit board layout that controls the ventilator’s functionality.

“They were very engaged and they were very good at what they did,” says Boire, describing the work of Janzen, Gowen and Pourhaj, in partnership with his own employees.

“I’m very proud that my team took this on, even though it was a little scary to jump into. It was a big confidence boost for them.”

Boire has since purchased equipment that allows RMD to build the circuit boards in-house and which he hopes will facilitate more collaboration between the college and RMD.

Janzen says the secondment made his summer busier than it normally would have been, but it was worth it.

“It was a bit of a sacrifice but at the same time, it was really impressive to see how RMD, and Jim Boire particularly, was putting his neck out there to get this thing done and put together. That sense of community was very strong and it was a really good thing to participate in.”

Though he and Gowen and Pourhaj already bring industry experience to their roles, the time at RMD has given them additional insight into the connection between theory and practice that they can bring back to the college to share with students.

“This experience, of course, has made us better at what we do,” he says.

"They've been rockstars."

At the beginning of May, as the project was ramping up, Boire needed more people. After the college’s Co-op Internship program put out the call, Boire interviewed six students, hired all of them, and then kept them extremely busy.

Among other things, they put together new vertical mills that would manufacture ventilator parts and constructed the ventilator assembly room. Because the ventilator was still in development, they had to sign non-disclosure agreements.

Boire says he impressed on the students the fact they were working on a brand-new medical device was something special, for RMD and for Saskatchewan.

“We were clear with them that this was different,” he says. “This is a never-happen-again-in-your-life moment. They had to grow up instantly. They were rock stars.”

After the assembly room was built within a couple of weeks, the quick pace continued, says Mitchell Theriot, one of the six summer students.

“Then we had to figure out how the process flows from the shop to that room, and how the inventory would work. So we really started with nothing in the room and ended up with ventilators there in a very short time,” he says.

By the time Theriot returns to school in September 2021 for his fourth year of mechanical engineering, he will have spent 16 months at RMD.

Over the past year, he has been involved in writing the work instructions and checklists for assembling the ventilators, which can be up to 44 pages long. “I feel I’ve gotten a lot more involved than an intern usually would. I’m really excited to have had this opportunity,” says Theriot, who is from Calgary.

A second mechanical engineering student, Micah Fenez, also spent 16 months at RMD. As someone who went into engineering with the goal “to learn how to build anything” he says working at RMD has been the perfect opportunity. “What I like about RMD is that it fits with what I want to do,” he says. “They can build anything: they have the equipment and the people that are capable of doing it.”

Along with Theriot, he’s had a hand in developing the stringent process needed to document each component of the ventilator, a necessity for medical certification. He also spent a significant amount of time last summer researching the flow meter, which controls the volume of oxygen delivered to the patient.

“Because we made the part ourselves, we had to determine every variable that affects that meter. It’s very humbling to know that you’re working on something that’s extremely critical,” says Fenez, a graduate of Saskatoon’s Legacy Christian Academy who will be working on third- and fourth-year classes when he returns to school this fall.

Both students feel their undergrad experience in the college has given them a basic foundation for their work at RMD.

“One thing post-secondary has really taught me is that you need to be able to work under pressure, to work under fairly large workloads,” says Theriot. “I think Engineering really shows you how to handle it.”

Fenez says he is particularly gratified to be working on a unique project, Saskatchewan’s only certified medical device. “As Jim puts it, nobody wants to design a pipe cleaner. We already have those. This is making a difference. It’s something that we need. It’s going to help people.”

Kresta is proud to see USask Engineering’s students step up and thrive in the RMD environment. “Well-trained engineers are critical thinkers who can work on complex problems, on teams where people have a range of experience and training,” she says. “In our program, we strive to give students a deep understanding of how ideas move from concepts to the marketplace. And we add hands-on experience so they are ready for the workplace.”

Boire says the workload and the responsibility at RMD was a challenging combination that all of the students met. Reflecting on Theriot and Fenez in particular, he says they made incredible gains in their attention to detail, thinking through tasks, and most importantly, recognizing if something was going wrong and reaching out for more information. “It’s kind of fun watching them grow up of over the course of a year. It’ll be neat to see how they do after this.”

"We can find local solutions."

After she visited RMD in March 2020 to learn about its plans to manufacture a ventilator in Saskatchewan, Kresta knew what had to happen next. Subject matter experts needed to be consulted, to ensure the final product would meet the needs of the medical professionals who would use it.

She’d already been on the phone with Preston Smith, dean of USask’s College of Medicine, to tell him about the project and secure his help in getting the right experts out to the RMD facility.

Smith’s conversations with Boire then led to Dr. Mateen Razzi, who is also the provincial department head of anesthesiology for the medical college and the SHA, checking out the ventilator and bringing in respiratory therapists and clinicians to test the machine and provide their feedback.

“At the end of the day, it’s a manufacturing process and the engineers are going to take the lead on that, but you can’t sell anything to anybody if the end user doesn’t like the product,” says Smith.

“It was a very, very cool story to be part of, to connect these people and get the right experts in the right place, advising the right people.”

In addition to the College of Medicine, contributions were made by other colleges as well.

“The university’s expertise was critical to pulling this off,” says Kresta.

The Western College of Veterinary Medicine’s Dr. Julia Montgomery, who is a respiratory subject matter expert, helped with writing the operation manual, testing of the machine function, the training video and the usability study.

College of Law professor Patricia Farnese helped with regulatory work on standards for medical devices related to the Health Canada submission.

USask Respiratory Research Centre members (director Donna Goodridge and an ICU nursing graduate student Rebecca Erker) wrote the ventilator training manual.

RMD team members had taken Edwards School of Business executive education courses on project management and executive leadership that were invaluable in carrying out the project efficiently and effectively under tight timelines.

-USask Communications

Both she and Boire believe the project could be a template for future collaboration between USask and industry.

“The university has to take a look at this and go, ‘Wow, this was very high profile, very fast-moving, and it worked. There was a very good result,’ says Boire. “How do we leverage that? How do we now make a pattern for something like this, so that we can have a set of criteria for industry partners that truly want to be a partner?”

USask Engineering is committed to helping drive innovation in the province, Kresta says, beyond the manufacture of medical devices. It already has close partnerships with SaskPower and with the province’s mining industry.

“When there are local problems, we can find local solutions. And these help us compete in a global economy that values these innovations as much as we do,” she says

Boire definitely supports nurturing closer integration between industry and academia, rather than writing a cheque and waiting for the results.

“We need to truly set ourselves up to be partners with the university and be collaborative, finding ways to hire students and find ways to do other research projects with each other.”

For his part, Boire has started a master’s degree that he is scheduled to complete in September 2022, unless it turns into a PhD project.

One supervisor is from the College of Medicine and the other is from the College of Engineering.

“If I want to be a partner with the university, I better put my right foot forward and show that I'm dedicated to this and that our company can do the research, and the manufacturing and the interaction with the different departments and colleges at the university.

“We should be ready to show that we want to partner because we want to grow technology inside Saskatchewan.”

"A product that will be used world-wide."

By the end of 2020, Saskatchewan’s provincial government had taken delivery of the first EUV-SK1 ventilators, after striking a deal to buy 100 units, to bring the total number of ventilators in the province to 650.

This spring, RMD was manufacturing training units – units that aren’t certified for hospital use – so staff can be trained on the EUV-SK1.

To this point, the company has kept the project low-key within the health-care industry and is instead looking more long-term.

“It is a year later now, so with vaccines coming out, what we’re focusing on now is not more sales, but getting these certified to full-service, full-use ventilators. That’s a big job,” Boire says.

“We’re going to be positioning ourselves for rural and remote areas, air ambulances and ambulances, so they have something more rugged and portable that they can take out and use. They don’t have that capability right now with an acute ventilator. Ours is an acute respiratory ventilator and it will have that ability.”

The journey will not be without hurdles. Companies like Boire’s must have an MDSAP (Medical Device Single Audit Program) certification, which is accepted by Health Canada and the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States. This requires third-party reviews of the device, which are paid for by the product developer.

The process is expensive, but doable, says Boire, who says the company has added at least a dozen employees the ventilator project has ramped up.

“What we’re trying to do is follow through on our ability to keep medical device manufacturing in the province with a product that will be used world-wide.”

The goal is to be more self-sufficient that next time manufacture of an innovative, high-level product is needed.

“Do you remember that feeling that you had in your stomach when they said the world is short of ventilators and then they showed all those people dying and then you found out that none of this stuff is made here?” Boire says.

“That's a terrible feeling and we want to bring quality manufacturing on high-end things back to Saskatchewan, in a way that's meaningful so the next time it isn't a big panic.”

In the year since Boire began developing the ventilator, the project has changed to set a new standard for USask collaboration with industry, inspired young engineers and changed the course of Boire’s company as well as his own career. And it began with one engineer reaching out to another.

“None of this would have happened if Suzanne hadn’t taken my call.”